The Surveillance State's Trojan Horse: Why Blue Springs' 'Flock Safe City' Drone Tech Is a Dangerous Precedent

Blue Springs, MO, just adopted Flock Safety's drone tech, but the real story isn't crime reduction—it's the normalization of ubiquitous government surveillance.

Key Takeaways

- •Blue Springs adopted Flock Safety's ALPR drone system, making it the first 'Flock Safe City' in Missouri.

- •The core controversy lies in the privatization of public surveillance infrastructure and data retention policies.

- •This deployment normalizes the expectation of ubiquitous digital tracking in suburban environments.

- •The technology sets a national blueprint for other municipalities seeking 'high-tech' crime solutions.

- •The long-term consequence is a chilling effect on anonymity and free movement.

The Hook: Welcome to the Panopticon, Courtesy of Your Local Government

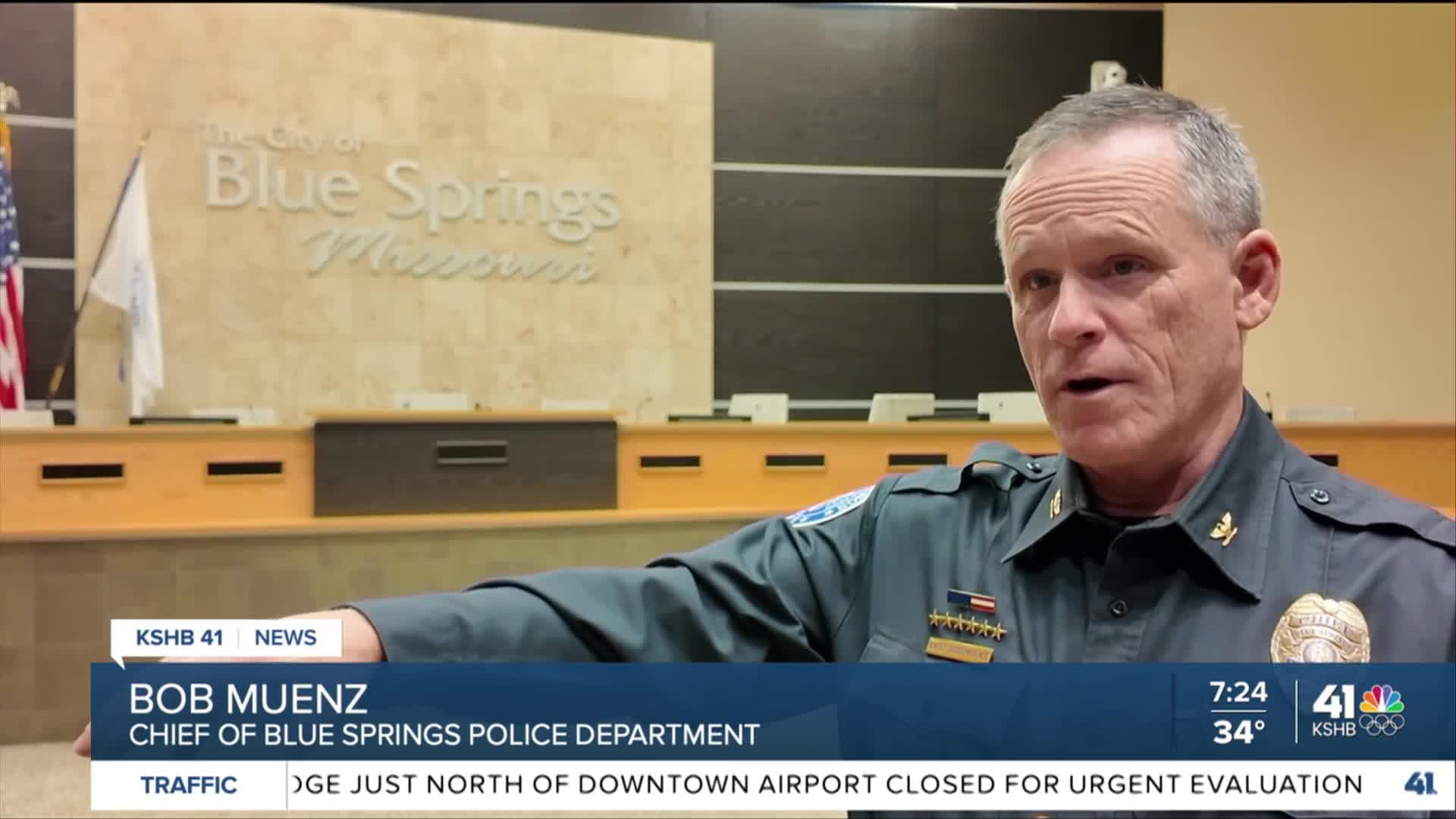

The news cycle loves a shiny new gadget promising public safety. Blue Springs, Missouri, has just been crowned the state's first 'Flock Safe City,' deploying sophisticated drone technology—specifically, Flock Safety's automated license plate readers (ALPRs) integrated with aerial surveillance. On the surface, this is pitched as a modern solution to petty crime and vehicle tracking. But as investigative journalists, we must look past the press release. The real story here isn't about catching a single stolen car; it's about the quiet, incremental erosion of public anonymity and the alarming speed at which municipal governments are adopting comprehensive, privatized surveillance infrastructure. This isn't just about public safety technology; it's about the future of privacy in American suburbs.

The 'Meat': Analyzing the Unspoken Deal

Flock Safety's system uses fixed cameras and, now, drones equipped with ALPRs that scan and log every license plate they see, regardless of whether that vehicle is connected to a crime. This data is stored, analyzed, and shared. The local police department gets an 'alert' when a plate associated with a warrant or a stolen vehicle passes by. This sounds efficient. Here's the catch: the system is provided by a private, for-profit entity. Who controls the data after the initial police query? How long is it stored? And crucially, what happens when this data is inevitably cross-referenced with other burgeoning datasets—facial recognition, social media monitoring, or future predictive policing algorithms?

The biggest winners here are not necessarily the citizens, but the tech vendors profiting from fear and outsourcing core governmental functions. We are trading genuine community policing for automated, passive data collection. The debate around drone surveillance rarely focuses on mission creep; it focuses solely on the immediate, narrow benefit. We are witnessing the creation of a permanent digital dragnet, funded by local taxes, operated by third-party contractors. This is a fundamental shift in the relationship between the citizen and the state, moving from targeted investigation to mass, preemptive monitoring. For more on the national trend of municipal tech adoption, see reports from the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

The 'Why It Matters': The Normalization of Digital Tracking

Blue Springs is a test case. If this deployment is deemed a success—even marginally—it creates a blueprint for every other mid-sized municipality struggling with budget constraints but eager to look 'high-tech.' This isn't just about license plates; it’s about establishing the *expectation* of being watched. Once the infrastructure is in place, the scope inevitably expands. Today, it’s ALPRs; tomorrow, it’s sophisticated computer vision analyzing pedestrian behavior. This constant, passive logging fundamentally chills free association and movement. Citizens begin to self-censor or alter their behavior knowing every trip, every visit, is now logged in a database. This chilling effect is the true cost of this automated surveillance.

Prediction: Where Do We Go From Here?

Within three years, expect a significant legislative push in states across the Midwest to standardize data retention policies for ALPR and drone footage, likely favoring law enforcement access over citizen privacy rights. Furthermore, expect a major vendor like Flock Safety to be acquired by one of the behemoths in defense or data analytics (think Palantir or a major telecom), instantly federalizing the local data streams. The suburbs will become the frontier for normalizing pervasive, AI-driven monitoring before major cities face the political backlash required to stop it.

Key Takeaways (TL;DR)

- Blue Springs adopted Flock Safety drones, marking a major step for municipal surveillance adoption in Missouri.

- The core risk is the normalization of passive data collection by private entities, not just targeted crime fighting.

- This sets a dangerous precedent for other suburbs looking to adopt similar, privacy-eroding technologies.

- The long-term threat is mission creep, where the data collected today is used for unforeseen purposes tomorrow.

Gallery

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a 'Flock Safe City' designation?

A 'Flock Safe City' is a municipality that partners with Flock Safety, a private company, to install their network of License Plate Readers (LPRs) and, in this case, drone-mounted readers, to capture and log vehicle data for law enforcement use.

Who owns the data collected by Flock Safety drones?

The data is managed through Flock Safety's cloud-based platform. While police use it for investigations, the data's handling, storage duration, and potential external sharing are governed by the contract between the city and the private vendor, often lacking robust public oversight.

Are drone license plate readers more intrusive than fixed cameras?

Yes. Fixed LPRs cover specific choke points. Drones offer dynamic, wide-area coverage, drastically increasing the volume and variability of collected data, making the surveillance inherently more pervasive and harder to track.

What legal precedent exists regarding ALPR data in Missouri?

Missouri has laws governing the use of ALPR data by law enforcement, but the integration of new aerial drone technology and private vendor data storage creates evolving legal gray areas that are often tested in court after deployment.